Vandersteen Quatro Wood loudspeaker

Richard Vandersteen was in good form at the 20th-anniversary seminar held by retailer Advanced Audio on November 11, 2006. When asked about his priorities in loudspeaker design, he sat erect in the seat next to me and thundered, "I will not [slams table with open hand] spend one red cent on cosmetics that I could have put into improving the sound of a loudspeaker!"

On one hand, I wasn't shocked. Vandersteen has long been known for his iconoclastic opinions on audio design —views that have led him to wrap his speakers in plain-looking "socks" rather than in exotic veneers. "I just don't think people have a clue what sonic price they are paying for having that acoustically reflective wood next to the drivers," he told me.

On the other hand, hadn't he just sent me a pair of his Quatro loudspeakers that were —how should I put this —clad in veneer?

"Well, our dealers begged me to make a version of the Quatro that looked more upscale," Vandersteen said. "I thought I could do it for a slightly higher price, so I just took a pair of Quatros off the line, squared off the edges, and wrapped them in veneer. We took it into the sound room, and it was just not the same loudspeaker. All that beautiful shiny veneer so close to the drivers had a catastrophic effect —I've known that for years, which is why we build speakers the way we do.

"Now we had a speaker that cost $1500 more and didn't sound as good as the fabric option. Initially, I added the new composite phenolic-epoxy plinth, which wasn't enough in itself, then I upgraded the tweeter, and we kept tweaking it until it was a little bit better everywhere than the fabric one —because I just wasn't going to charge more for a speaker that didn't deliver more. Ultimately, we got a speaker that was noticeably better, but it wasn't a $1500 upgrade, it was $3700."

That means the Quatro Wood sells for $10,700/pair. Some speaker manufacturers won't even cross the street for that little money.

The field has sight, and the wood a sharp ear

The Quatro Wood is based on the Quatro, which Michael Fremer reviewed in July 2006. It's still a first-order, four-way design that includes an internal subwoofer with a 250W amp and two 8" carbon-loaded cellulose-cone drivers. The midbass and lower midrange (100 –900Hz) are handled by the same 6.5" woven-fiber cone driver Vandersteen designed for the fabric Quatro, but the upper midrange and low treble (900Hz –5kHz) and upper frequencies (5kHz to "beyond 30kHz") are handled by drivers based on those in the Vandersteen 5A.

The midrange driver is Vandersteen's patented 4.5" open-basket design, featuring a woven composite driver and cylindrical alnico-magnet structure —which allows Vandersteen to vent much of its rear wave into "a transmission line to prevent those reflections from interfering with the direct sound." The driver's chassis is invested metal, as opposed to the regular Quatro's filled nylon—which, Vandersteen remarks, "delivers a bigger sonic dividend than you'd expect."

The 1" ceramic-coated, alloy-dome tweeter is a tuned dual-chamber design, also transmission-line loaded. Vandersteen says he chose that acoustic damping and a precision phase plug to extend its high frequencies "past audibility without the excessive ringing associated with open or underdamped metal-dome tweeters."

The other critical difference is that composite phenolic epoxy plinth, which Vandersteen says is unbelievably inert —and ungodly expensive. "A 4' by 8' sheet costs $1000, and then it has to be milled like aluminum, although at even slower speeds."

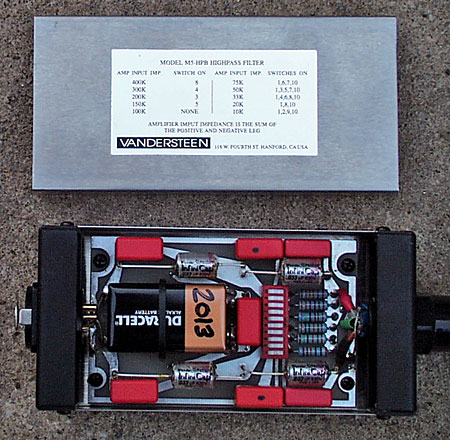

The Quatro Wood shares the Quatro's adjustable EQ network and its battery-biased, passive high-pass filter, but since Vandersteen claims most people don't understand this approach, I should perhaps speak of it a bit more.

The Quatro has a terminal strip on its rear panel that accepts two sets of speaker cables. (Another example of Richard Vandersteen's refusal to bow to convention: "I've tested all the expensive binding posts and [terminal strips] still sounds best.") One set feeds the subwoofer and mid-bass (everything below 900Hz); the other feeds 900Hz and above. However, unlike conventional designers, Vandersteen rolls off the bass below 100Hz with a passive, first-order filter that sits between preamp and amplifier. The balanced module costs $795; the single-ended version goes for $695.

"The ultimate advantage of using a high-pass filter is increased transparency in general, because you're getting the deep bass out of the amplifier and the midrange and HF drivers," Vandersteen said. "Now, if I'd put only a powered sub in there, the 6.5" driver would be flopping around like crazy because it's getting all the bass —not to mention the [intermodulation] and the heating up the voice-coil, which leads to thermal compression —and it's just a big old can of worms. You're putting power into a driver that just can't respond to it. Now put a high-pass filter in there, and you clean all of that up."

The powered subwoofer, which is fed from the passive woofer terminals, thus has to be re-equalized to get back that mid- and low-bass energy. It actually incorporates an 11-band equalizer, to allow the best integration to be obtained with the owner's room acoustics.

Without touch we are but hunks of wood

The Quatros are a tad more complicated to set up than most loudspeakers. Fortunately, your audio dealer should be the one having to do that job. The high-pass filters need to be set for your amplifier's input impedance via internal DIP switches. The speakers are then located within the room for optimal midrange coherence, and the woofer's 11-band EQ is calibrated using an SPL meter and Vandertones, a CD Vandersteen supplies his dealers. In this two-person process, one participant sits in the sweet spot with the meter and the other dials in each of the EQ bands on the speakers' rear panels. Each speaker is tuned separately. After adjusting the EQ, you tune in the amount of bass reproduced with the woofers' level controls. Vandersteen says that customers who buy the Quatros used and have no Vandersteen dealer to set them up can substitute the warble tones on Editor's Choice (CD, Stereophile STPH016-2) for Vandertones; the owner's manual posted on his website has the instructions.

The final setup chore is adjusting the speakers' rake, so the signal is time and phase coherent at the listening position. "For time- and phase-aligned designs, the vertical height of the drivers in relation to the listening position is vital," Vandersteen said. "You can have a huge horizontal window if you address the tilt correctly. We believe that waveform preservation is crucial."

To communicate the subtlest universal truths by means of wood, metal, and vibrating air

As Art Dudley is wont to say, Jethro H. Tull! Vandersteen wasn't kidding about that huge horizontal window, as I discovered on listening to Paavo Järvi and the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra's recording of Elgar's Enigma Variations (SACD, Telarc SACD-60660). The soundstage was immense —both wide and deep. Not only was the CSO's bass section hefty and solid, but the acoustic of Music Hall was almost frighteningly detailed —a sure sign of clean deep-bass response, in my experience.

The percussion and brass fortissimo in Variation VII almost propelled me physically deeper into the room. If you want to hear orchestral power, the Quatro Wood ought to rocket onto your list. At the same time, the strings had delicacy, sheen, and gloss that were convincing and extended.

That high-frequency smoothness and extension were put to the test with the Hot Club of San Francisco's Yerba Buena Bounce (CD, Reference RR-109CD). On track 1, "Mystery Pacific," violinist Evan Price and solo guitarist Paul Mehling leapt into the stratosphere with flurries of notes over the chugging rhythms of bassist Ari Munkres and guitarists Jeff Magidson and Jason Vanderford, and never came down for air until the disc was done.

Price's quicksilver fiddle was bright and bold, but never astringent. Oh, there were gobs of harmonic overtones shooting off the fundamentals, indicating beaucoup HF extension, but Price's tone was sweet and plangent. And, oh momma, is Mehling ever one fast-fingered guitarist! Whooowee, what runs, what flurries —and the Quatro Wood sorted them out with panache.

For female vocals, I've heard few speakers that equal the Quatro Wood. Jacqui McShee's pure soprano on "Willy O'Winsbury," from Pentangle's Solomon's Seal (CD, Castle 555), was butter. Its purity and transparency were rivaled only by the solidity of the sonic image —which was life-sized and present. If you can remain unmoved after hearing this Child ballad through the Quatros, you've a heart of stone (and ears to match, I fear).

Male vocals, particularly baritones, did not fare quite as well. Listening to John Cale's "Sylvia Said," from his The Island Years (CD, Island 524235), I found his voice lacked body. Cale's voice may be an acquired taste, but it's one I acquired in 1970, and I know that voice about as well as I know that of anyone I have never actually met. It may have vast crevices, but it's rooted in a definitely physical body —and that body was less than present through the Quatros. Cale's bass burbled and bubbled along at the bottom, quite full of zest and punch, and much of his upper range sounded perzackly as it ought, but his chest tones lacked a degree of punch and, oddly, drive.

That slight loss of propulsion was also evident on Sugar Hill: The Music of Duke Ellington and Billy Strayhorn (SACD, Chesky 333), particularly in Javon Jackson's tenor saxophone sound, which is quite warm and full-bodied. It continued to have warmth and heft through the Quatro Woods, but was slightly smaller —the burr of Jackson's upper octaves was intact, as was the growl of his deepest notes, but there was a loss of energy that seemed to diminish his contribution ever so slightly. Tony Reedus' drums do have heft and drive, and Paul Gill's bass digs deep and pushes along splendidly, so I'm not talking about a complete loss of physicality or drive —just an area where the Quatro is neither as transparent nor as invisible as throughout the rest of its range.

One other minor quibble —and I do mean minor —is that you optimize the Quatros for your seated listening position, which is fine: That is, after all, where I do my critical listening. One afternoon, however, I decided to listen to The Allman Brothers at the Fillmore East: 1970 (CD, Grateful Dead 4063), and once Duane kicked into "Statesboro Blues," I couldn't sit still any more. I ran downstairs and grabbed my Telecaster out of my office, deciding (immodestly and illogically) that what the recording needed was a third guitarist.

Standing, attempting to find a rhythm groove, I found myself much less compelled to move, bop, and participate. The high frequencies were more pronounced, and much of the "presence" had evaporated. Hmmm, I thought. This is the difference you get when you become a participant rather than an observer. I sat down to ponder that, and suddenly everything popped back into focus and I leapt to my feet —only to sit back down again.

Yes, Vandersteen's adherence to "waveform preservation" does lock you into an optimal listening position, but, as he pointed out to me one day, many loudspeakers don't even give you that. The reason it took me so long to notice that the Quatros lost some of their magic when I stood up was that they pretty much pinned me to my seat when I was listening.

Two roads diverged in a yellow wood

I've had a passel of high-end speakers pass through my listening room in the last year, but the obvious point of comparison for the Quatro Wood was the Wilson Audio Specialties WATT/Puppy 8; not because the two speakers are similarly priced (the W/P8 costs $27,900/pair), but because they're almost identical in size and, I suspect, aspiration —meaning both offer optimum balances of excellence and price within their respective lines. Also, I hadn't yet shipped the W/P8s back to Wilson.

Elgar's Enigma Variations sounded immense through both pairs of speakers, but more forward through the Wilsons; the Quatros weren't so much more laid-back as smoother. Part of this was the more relaxed sound of the Quatros' highs, but a mild loss of upper-midbass energy may have also contributed. In terms of deep bass and slam, the two were amazingly close, although the Quatros' deepest tones were noticeably tighter.

The Hot Club of San Francisco's "Mystery Pacific" chugged along with a tad more immediacy through the W/P8s. They reproduced a sense of momentum that the more relaxed Quatros did not quite match. On the other hand, the Wilsons put a little more rosin on Evan Price's bow, giving his fiddle a sharper sound than did the Vandersteens —which, without reducing extension or harmonic overtones, made him sound sweeter and smoother.

"Sylvia Said" sounded more like the John Cale I know through the W/P8s —his voice projected his size and power, while the Quatros slimmed him down a weight class. The Vandersteens delivered a smoother, calmer Cale —which, oddly enough, has actually happened over the years, but had not when he recorded this track. I did think the sound of the organ and Cale's viola had a more plaintive sound through the Quatro Woods, however.

Sugar Hill had more Javon Jackson through the WATT/Puppys —not an immense amount, but there was more honk in his tenor. It didn't change his sax into a soprano, but there was a difference in perspective and power through the Vandersteens. Gill's bass did seem more propulsive through the Vandersteens, although in general, the Wilsons had a bit more bouncy energy throughout the comparison.

And yes, I did manage to add a Tele to the Allmans' Fillmore East: 1970 with the Wilsons. I can't play rock'n'roll sitting down —I don't develop the full extent of my guitar face sitting down, so I have to stand, which the W/P8s accommodated better than the Quatros. Strangely, my playing still sucked.

By and large, the Vandersteen Quatro Wood is a worthy competitor to the Wilson WATT/Puppy 8, which is high praise. In fact, if you've auditioned the Wilson and found it a bit too present and punchy, the Quatro Wood might be precisely the speaker you're looking for.

Heap on more wood

I adored the Vandersteen Quatro Wood. It isn't perfect, but no speaker is. The slight tonal shift in its lower-midrange/upper-midbass area was noticeable, but no more annoying than other highly lauded loudspeakers' HF tilt or slight bass bloat —indeed, to some ears, far less so.

What the Quatro Wood did well, it did so well that I find it easy to forgive its shortcomings. When the speakers were tuned to my room, they had deep, tight bass that really recreated the majesty of music's foundation. They delivered a huge, detailed, transparent soundstage that gave me all of the music without obscuring any of its details. And I found the speaker's representations of female voices, stringed instruments, and ambient detail about as good as those of any speaker I've ever heard —which, from an old Quad owner, is high praise indeed.

Factor in price, and you've really got something. Eleven grand ain't cheap, but the Quatro Wood is essentially handmade, and its levels of build and engineering are extremely high. All of its drivers are designed and/or built by Vandersteen, and it features unique technologies, such as its transmission-line backwave loading, that other speaker manufacturers haven't even thought about. All of that come at a price, but the other speakers to which I would compare it cost two and three times more.

Richard Vandersteen, an American classic himself, has come up with a speaker as forthright and down to earth as he is. That's really saying something [slaps table with open palm].